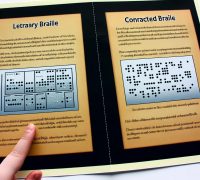

Understanding Literary and Contracted Braille

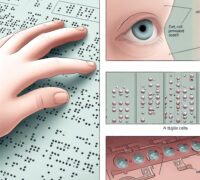

Braille is a tactile writing system used by individuals who are visually impaired or blind, allowing them to read and write through touch. Within this system, there are different versions, primarily known as literary braille and contracted braille. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for educators, caregivers, and individuals who are learning or teaching braille.

What is Literary Braille?

Literary braille is essentially the uncontracted form of braille. This means that each character in a word is represented by a distinct set of raised dots, with no shortcuts or abbreviations. It closely mirrors print text in other languages, where each letter corresponds directly to a braille cell. Literary braille is often used for beginners as it presents braille in its simplest, most straightforward form. It emphasizes clarity and is ideal for those learning the basics of braille reading and writing.

Key Features of Literary Braille

In literary braille, emphasis is placed on ensuring that each letter and number is represented distinctly. This clear correspondence aids in comprehension for learners and allows detailed reading of texts, such as novels and educational materials. While it is suitable for foundational learning, literary braille can be bulkier and require more space when compared to contracted braille. The system involves a linear approach where readers can find an almost one-to-one equivalence between the braille language and other written languages, reflecting every print character to its equivalent braille cell combination.

The Educational Role of Literary Braille

Literary braille acts as an educational foundation for new learners of braille, providing an environment free from complexities. This straightforwardness permits a focus on learning braille literacy thoroughly, making it easier to grasp without the immediate pressure of learning contracted forms, which demand an understanding of numerous abbreviations and contractions. In educational settings, literary braille is central because it supports thorough learning and facilitates a smoother transition into more advanced braille systems.

What is Contracted Braille?

Contracted braille, previously known as Grade 2 braille, is a compressed form of braille that utilizes contractions—abbreviations of words and common letter combinations. This system is designed to reduce the physical space required to write and thus allows for more efficient reading and writing.

Understanding Contractions in Braille

In contracted braille, combinations of letters or entire words are represented by a single cell or a series of cells. This practice significantly reduces the number of cells needed to convey text, making it faster to read. For example, the word “and” might be represented by a single cell, rather than three separate cells for ‘a’, ‘n’, and ‘d’. This efficiency allows readers to digest written material quickly, thereby opening avenues to a wide range of reading materials and forms communication within limited space.

Efficiency and Usage

Because of its efficiency, contracted braille is more suitable for advanced braille readers and is often utilized in everyday reading materials, such as magazines and newspapers. It requires a deeper understanding of the various contractions and rules, and can thus be challenging for newcomers without prior knowledge of braille reading. Contracted braille extends beyond merely reducing space; it streamlines the reading and writing process, enabling quicker comprehension and faster scanning ability when used in larger texts or casual reading environments.

Choosing Between Literary and Contracted Braille

The choice between literary and contracted braille largely depends on the reader’s proficiency and the context in which braille is being used. Literary braille is a stepping stone, providing foundational skills and understanding, while contracted braille is a practical tool for extensive, day-to-day reading. Educators and learners should assess the needs and capabilities of each individual when deciding which system to adopt.

Factors Influencing the Choice

The decision between literary and contracted braille should consider several factors. Primarily, the choice should be tailored based on the learner’s age, cognitive capacity, and learning goals. Young learners or individuals just beginning their journey in braille literacy often benefit from the uncontracted system’s straightforwardness. On the other hand, for those who have achieved fundamental proficiency, moving onto contracted braille is a logical next step, providing seamless integration into daily reading activities and access to broader resources.

The Role of Educators and Caregivers

Educators and caregivers play a pivotal role in this transition. They can assess progress and adapt learning materials to ensure comprehension and engagement. Understanding an individual’s learning pace and offering continuous support and encouragement allows a person to advance their braille skills effectively. These educators can simplify this progression by gradually introducing contractions and accompanying rules, aligning with the learner’s growing familiarity with braille. Furthermore, integrating a mix of real-world reading materials, such as menus or bills in contracted braille, with literary braille instructional materials can provide practical exposure and experience.

Advantages of Mastering Both Systems

Being proficient in both literary and contracted braille can be highly advantageous. It equips individuals with flexibility in varied reading scenarios, allowing navigation through comprehensive educational materials, while keeping pace with leisure reading, often presented in contracted version for brevity. For instance, literary braille remains indispensable when tackling technical publications where explicit detail is necessary, whereas contracted braille frequently complements social and leisurely reading, minimizing volume and improving portability.

Learning Resources and Materials

For further resources on braille learning and materials, some organizations specialize in braille education and can be a valuable asset. Consider reaching out to educational institutions that offer support for visually impaired learners for more detailed guidance. Institutions may offer courses or workshops specifically designed to cater to all age groups and learning levels, which can significantly enhance learning outcomes and familiarity with both literary and contracted braille.