Introduction to the Braille Alphabet

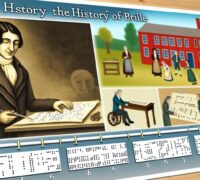

The Braille system is a tactile writing method employed by individuals who are visually impaired. This innovative approach was crafted by Louis Braille in the early 19th century. Over the years, it has become an indispensable tool for literacy among those who are blind, enabling them to access not only literary content but also information vital to daily living and educational growth.

The Basics of Braille

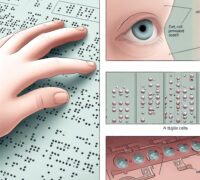

Braille isn’t simply a language unto itself. Rather, it functions as a code. Through it, multiple languages can be transcribed and read. Comprising a series of raised dots, Braille is organized into cells, each capable of holding up to six dots arranged in a 2×3 grid. This configuration allows for a myriad of patterns, each representing different letters, numbers, or punctuation marks.

Understanding Braille Cells

Each character in Braille, referred to as a cell, includes six potential positions where dots can either be raised or remain flat. The existence or nonexistence of a dot in any given position forms distinct characters. For example, the simple letter ‘A’ can be formed using just a single dot positioned in the upper left corner of the Braille cell.

Reading and Writing Braille

In traditional contexts, reading Braille involves the gentle sweeping of one’s fingertips from left to right over lines of text. The act of writing Braille, on the other hand, may be accomplished using a slate and stylus. This device facilitates the manual embossing of each dot. Alternatively, technology such as the Perkins Brailler, a Braille typewriter, can be employed for the same purpose, catering to those preferring a mechanical method of writing.

Modern Tools and Accessibility

Recent technological strides have ushered in devices like Braille displays and notetakers. These modern tools can adeptly convert digital text into Braille, thereby broadening the spectrum of content accessible to users. Should you desire a deeper dive into Braille technology, institutions such as Perkins School for the Blind offer a wealth of resources.

The Importance of Braille Literacy

Braille literacy stands as a cornerstone for education and autonomy among those with visual impairments. Mastery of this system empowers individuals, allowing for effective reading and writing. In turn, this proficiency enhances their capability to communicate and to engage with educational contents more thoroughly.

Integration in Education Systems

Numerous educational systems have integrated Braille instruction into their curricula for students who are blind. Typically introduced at an early age, developing a foundational aptitude in Braille is essential. It is crucial not only for academic triumph but also for pursuing higher education and subsequent career opportunities.

Braille in Everyday Life

The application of Braille extends beyond textbooks and reading materials. It is also present on essential public signage, ATM keyboards, and various product packaging. This omnipresence supplies vital information, thus significantly enhancing accessibility for those with visual impairments.

Challenges and Misconceptions

Regrettably, Braille is often subject to misconceptions. A common erroneous belief is that learning Braille is exceedingly difficult or that it has become antiquated due to the rise of audio technology. In truth, Braille remains a critical and irreplaceable instrument, particularly for literacy and nuanced note-taking.

Promoting Braille Awareness

Efforts to elevate awareness and literacy of Braille are constantly in motion worldwide. Numerous organizations, devoted to aiding the visually impaired, actively conduct workshops, organize campaigns, and host events aimed at underscoring the paramount significance of Braille education. An example of such an organization is The American Foundation for the Blind, which offers support and resources for those engaging with Braille.

By grasping and valuing the contribution of the Braille system, society becomes better equipped to support individuals who depend on this essential form of communication. Understanding its role and benefits can potentially pave the way toward enhanced inclusivity and accessibility for visually impaired individuals in different areas of life.